Decoding DNA: From the Double Helix to the Central Dogma

After nearly a century of contemplation and verification by scientists, it was confirmed: DNA is the hereditary material.

However, new questions emerged: Why DNA? How can such a microscopic molecule carry genetic information so vast and precise?

DNA is composed of only four simple deoxyribonucleotide molecules, yet it must describe the entire spectrum of an organism's traits. It is akin to asking a pen that can only write the letters "A, B, C, and D" to compose the epic masterpiece War and Peace. The mystery, far from being solved, only grew more profound.

The history of science is never short of turning points.

In 1953, a magical configuration leaped out from the blurry shadows of X-rays: the DNA double helix structure. James Watson and Francis Crick drew inspiration from the X-ray diffraction patterns of DNA crystals captured by crystallographers Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin, successfully constructing the mysterious yet elegant double helix model.

Two strands intertwined, with "letters" pairing in the simplest possible way: A with T, and C with G. Like buttons. Like a key finding its lock. Like a pair of dance partners who never miss a step. It is precisely these base-pairing rules that allow DNA to structurally carry and replicate information.

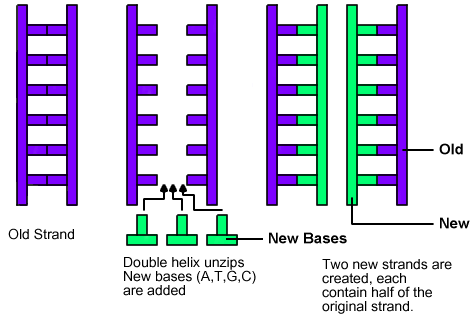

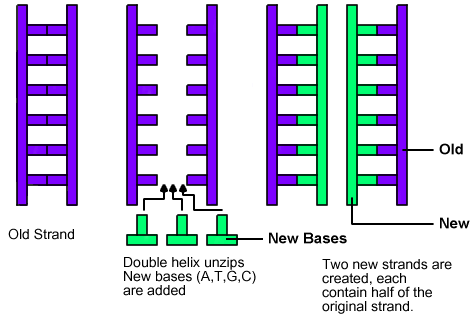

While observing the model, Watson proposed a bold hypothesis: DNA replicates in a semiconservative manner. The two original strands unwind, with each being passed to one of the two offspring, subsequently generating two new strands identical to the parent. But how could this be proven? And why must DNA adopt this "half-old, half-new" mode of replication?

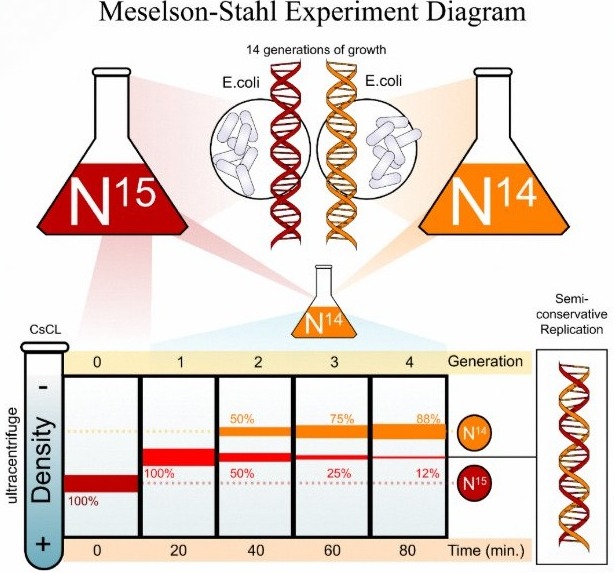

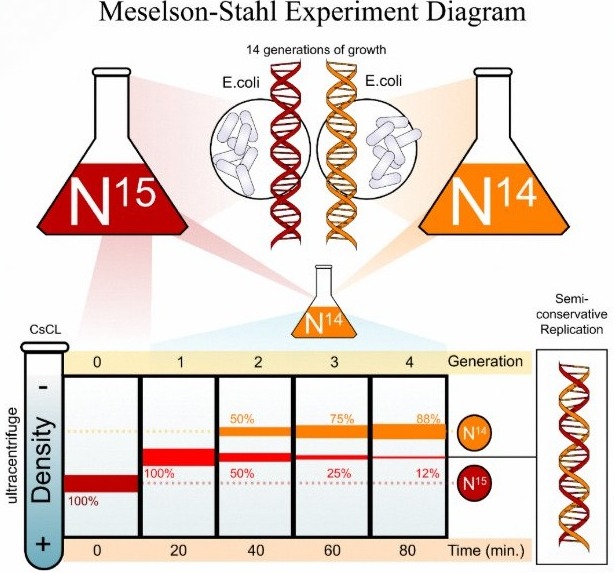

In 1958, Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl provided the answer. They designed and executed what would later be hailed as one of "the most beautiful experiments in biology."

Building upon the ingenious design of the Hershey-Chase experiment, they utilized the weight differences between isotopes to culture bacteria. After growing several generations in a medium containing the N-15 isotope, they transferred the bacteria to a medium containing N-14. From that point on, any DNA replication could only utilize the N-14 isotope.

By comparing the density of the DNA molecules across generations, Meselson and Stahl reached the only logical conclusion: In every cycle of division, the DNA in the daughter bacteria consists of a double helix formed by one parental strand and one newly synthesized strand. Semiconservative replication thus received irrefutable experimental evidence.

However, new questions emerged: Why DNA? How can such a microscopic molecule carry genetic information so vast and precise?

DNA is composed of only four simple deoxyribonucleotide molecules, yet it must describe the entire spectrum of an organism's traits. It is akin to asking a pen that can only write the letters "A, B, C, and D" to compose the epic masterpiece War and Peace. The mystery, far from being solved, only grew more profound.

01

The Emergence of the Double Helix: Structure Reveals the Secrets of Information

The history of science is never short of turning points.

In 1953, a magical configuration leaped out from the blurry shadows of X-rays: the DNA double helix structure. James Watson and Francis Crick drew inspiration from the X-ray diffraction patterns of DNA crystals captured by crystallographers Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin, successfully constructing the mysterious yet elegant double helix model.

Two strands intertwined, with "letters" pairing in the simplest possible way: A with T, and C with G. Like buttons. Like a key finding its lock. Like a pair of dance partners who never miss a step. It is precisely these base-pairing rules that allow DNA to structurally carry and replicate information.

While observing the model, Watson proposed a bold hypothesis: DNA replicates in a semiconservative manner. The two original strands unwind, with each being passed to one of the two offspring, subsequently generating two new strands identical to the parent. But how could this be proven? And why must DNA adopt this "half-old, half-new" mode of replication?

Figure 1. The semiconservative DNA replication model

02

Truth Under Density Gradient: Semiconservative Replication

In 1958, Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl provided the answer. They designed and executed what would later be hailed as one of "the most beautiful experiments in biology."

Building upon the ingenious design of the Hershey-Chase experiment, they utilized the weight differences between isotopes to culture bacteria. After growing several generations in a medium containing the N-15 isotope, they transferred the bacteria to a medium containing N-14. From that point on, any DNA replication could only utilize the N-14 isotope.

By comparing the density of the DNA molecules across generations, Meselson and Stahl reached the only logical conclusion: In every cycle of division, the DNA in the daughter bacteria consists of a double helix formed by one parental strand and one newly synthesized strand. Semiconservative replication thus received irrefutable experimental evidence.

Figure 2. The Meselson-Stahl experiment

At this point, the clues of a century were finally connected: From Mendel’s peas to Griffith’s mice; From bacteriophage infections to the mysterious "X" captured by X-rays; These fragmented clues, like a vast net, were drawn tight through successive experiments, finally capturing the "figure" hidden in the depths of life: DNA.

03

The Next Challenge: From Base Sequences to Biological Traits

However, a new question followed: "How does the sequence of bases in DNA determine traits?" Once genetic information is written into DNA, how is it "read" by the cell? The answer lay in another class of molecules that had once been overlooked by early geneticists: Proteins.

Compared to DNA, which is composed of only four simple nucleotides, proteins are far more complex. Proteins possess unpredictable three-dimensional structures; they can fold, bend, and catalyze chemical reactions. Our understanding of proteins predates our understanding of DNA by many years..

While Watson and Crick were building the DNA model, their colleagues Max Perutz and John Kendrew were attempting to analyze the 3D structure of protein molecules. Success for these two scientists came a bit later; in 1959, they successfully resolved the 3D structure of hemoglobin, revealing for the first time the high degree of protein complexity..

This discovery was timely. Only after DNA was confirmed as the carrier of genetic information did it make sense to ask: How does the relatively simple DNA guide the cell in synthesizing such a diverse and functional array of proteins?

04

Deciphering the Code

Surprisingly, the first logical step toward solving this puzzle was taken on scratch paper rather than in a petri dish.

Physicist George Gamow, a key figure in the Big Bang theory, speculated that the four bases must be organized in a specific pattern to correspond to the 20 amino acids in proteins.

If two bases corresponded to one amino acid (4²), the combinations were insufficient.

If four bases corresponded to one amino acid (4⁴), it seemed redundant.

Only three bases (4³=64) provided just enough coding space.

In 1961, Marshall Nirenberg and Johann Matthaei cracked the first codon: UUU → Phenylalanine. However, strictly speaking, their experiment only proved that DNA sequences corresponded to amino acid sequences; it did not prove the exact number of bases per amino acid.

Har Gobind Khorana provided the solution. Using more complex long-chain nucleic acid sequences, he proved that only a triplet sequence could correspond to a single amino acid. Over the next five years, scientists from various institutions worked together to decode all combinations: 64 codons corresponding to 20 amino acids—an unbelievably elegant design.

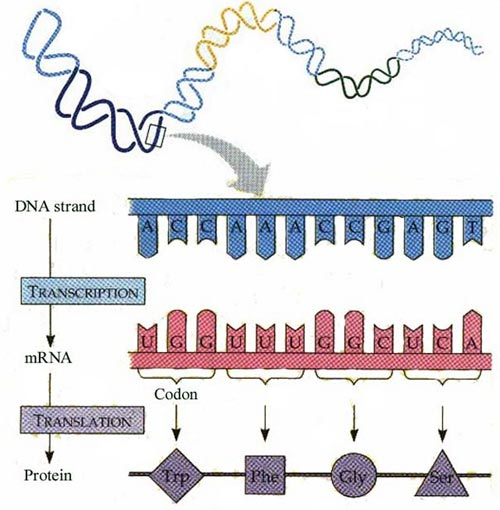

Figure 3. The central dogma

Now, returning to that yellow pea, we can finally trace the entire process in reverse: The pea contains a protein that determines the formation of its surface pigment. The sequence of amino acids for this protein is written in the pea’s DNA, with three bases corresponding to each amino acid.

DNA does not directly participate in protein synthesis. In the cell, genetic information must first be "transcribed" into an intermediate molecule—RNA. RNA then "translates" the base sequence into an amino acid sequence to synthesize a protein.

DNA stores information, RNA translates it, and proteins execute it..

This is the Central Dogma. The Central Dogma is like the main melody of life’s operation; every cell sings according to this rhythm. By understanding this pathway, humanity can finally explain the origin of hereditary traits, identify the roots of genetic diseases, and begin to envision precise, limited interventions within this flow of information.

Life may be vast and complex, but its underlying logic has finally been understood, written, and gradually mastered by humankind. And the exploration of genes continues.

At EDITGENE, our custom gene knockout cell line services utilize an advanced CRISPR/Cas9 system to support research teams in bridging basic research and clinical applications. Feel free to reach out anytime to design a gene editing plan tailored to your research needs.